JOHN MANGELS, The Plain Dealer, December 19, 2010

In the four decades since Ohio National Guardsmen fired on students and antiwar demonstrators at Kent State University, Terry Norman has remained a central but shadowy figure in the tragedy.

In the four decades since Ohio National Guardsmen fired on students and antiwar demonstrators at Kent State University, Terry Norman has remained a central but shadowy figure in the tragedy.

The 21-year-old law enforcement major and self-described “gung-ho” informant was the only civilian known to be carrying a gun — illegally, though with the tacit consent of campus police — when the volatile protest unfolded on May 4, 1970. Witnesses saw him with his pistol out around the time the Guardsmen fired.

Though Norman denied shooting his weapon, and was never charged in connection with the four dead and nine wounded at Kent State, many people suspected he somehow triggered the soldiers’ deadly 13-second volley.

In October, a Plain Dealer-commissioned exam of a long-forgotten audiotape from the protest focused new attention on Norman. Enhancement of the recording revealed a violent altercation and four gunshots, 70 seconds before the Guard’s fusillade. Forensic audio expert Stuart Allen said the shots are from a .38-caliber pistol, like the one police confiscated from Norman minutes after the Guard shootings.

The newspaper’s subsequent review of hundreds of documents from the various investigations of Norman, including his own statements, and interviews with key figures, uncovered more surprising information:

• The Kent State police department’s and FBI’s initial assessment of Norman was badly flawed, with failures to test his pistol and clothing for evidence of firing, to interview witnesses who claimed Norman may have shot his gun and to pursue the question of whether it was reloaded before police verified its condition.

• The Kent State police detective who took possession of Norman’s pistol, and whose investigation ruled out its having been fired, was directing Norman’s work as an informant and later helped him get a job as a police officer.

• Norman’s various statements about why he drew his pistol are inconsistent on some important details and are contradicted by other eyewitnesses. Also, Norman would barely have had time for what he claims to have done during that crucial period.

• Kent State officers knew Norman regularly carried guns, including on campus, even though the department’s chief and another local law enforcement official had doubts about Norman’s maturity and self-control.

• The FBI initially denied any connection with Norman, although the bureau had paid him for undercover work a month before the Kent State shootings. His relationship with the FBI may have begun even earlier than Norman has acknowledged, and he may later have had ties to the CIA.

• After the May 4 tragedy, Norman transformed from informant to cop to criminal.

Antiwar protest builds on Kent State campus

The tolling of Kent State’s Victory Bell, signaling the start of the antiwar protest, drew Norman to the commons just before noon on Monday, May 4, 1970

A camera hung from his neck. He wore thick-soled “trooper boots,” a gas mask he’d bought at a police supply store and a nickel-plated .38 in a holster hidden under his sport jacket.

He said he carried the snub-nosed, five-shot Smith & Wesson for protection. Norman was well known to campus activists, whose meetings he had begun trying to infiltrate in 1968, soon after he arrived as a student.

Norman’s conservative, law-and-order outlook clashed with the militantly anti-war, anti-authoritarian politics of groups like the Students for a Democratic Society. He showed up at their gatherings, trolling for information and snapping pictures until he was tossed out. He said he hoped the photos he regularly provided to the Kent State police department would help send activists to jail.

Throughout the weekend, Norman photographed the increasingly raucous protests at the request of campus police Detective Tom Kelley, his regular contact.

He carried his pistol Sunday night, while photographing demonstrators, and again Monday when he headed for class, with plans to take pictures at the noon anti-war rally. Norman said Kelley and FBI Agent Bill Chapin of the bureau’s Akron office asked him to attend, and either Kelley or Chapin had given him film.

As the Guardsmen moved out, with orders to sweep protesters off the commons and over Blanket Hill, Norman stuck close.

When the soldiers topped the hill and reached a football practice field on the other side, the protesters’ rock-throwing intensified. Norman moved inside a protective semi-circle of Guardsmen, waiting with them as officers discussed what to do.

Several times, Norman hurled stones back at demonstrators. He caught the attention of Guard Capt. John Martin, who wondered, “My gosh, where did that idiot come from and what’s he doing there?”

Finally, a commander ordered the Guardsmen to double-time back up Blanket Hill. Norman said he’d been preoccupied photographing some rock-throwers and missed the soldiers’ departure. He slipped into the crowd, hoping to blend in with several news photographers.

Terry Norman’s statements to police vary

What Norman did next remains in dispute.

Norman said that as the retreating Guardsmen neared the crest of Blanket Hill, he saw them halt, crouch and level their rifles. Like several other witnesses, Norman reported hearing a sharp sound, either a firecracker or perhaps a small-caliber gunshot, followed almost instantly by a torrent of Guard bullets.

He said he dropped to the ground and heard a round go over his head. That would place him on a slope south of Taylor Hall, near the Guard’s line of fire.

After the volley, Norman either “stayed put for a couple of minutes,” started for the campus police station, or headed up the hill toward the shooting site to take more photos, depending on which of his various statements to Kent State police, the FBI, the State Highway Patrol and lawyers one follows.

Norman said he then knelt to check on a “hippie-style person” whom he saw fall or whom he found lying on the ground. In some accounts, the downed man was bleeding from the face; in others, he was overcome by tear gas and his nose was running.

Norman said he moved to leave after determining the man was OK, but he was attacked. In one statement, he was chased and tackled by a group of demonstrators angered by his picture-taking. In others, his initial assailant was a man who grabbed for his camera and gas mask while someone else clinched him from behind.

Norman said he was pulled to the ground and “completely surrounded” by protesters chanting “Kill the pig!” and “Stick the pig!” In a couple of his statements, he claimed to have been hit by rocks and pummeled by fists.

He pulled his pistol (either from his holster or his pocket, depending on the statement) and told his attackers to back off or they were “going to get it.” He struck an assailant with his gun in some accounts but didn’t mention that in others. Then he said he ran down Blanket Hill and across the commons to seek shelter with the Guard, which had set up a secure area.

There, chased by two campus officials who yelled that Norman had a gun and may have shot someone, he surrendered his pistol to a Kent State police officer. A TV cameraman filmed the turnover. “The guy tried to kill me!” Norman says, agitated and panting. “The guy starts beating me up, man, tries to drag my camera away, hit me in the face!”

At no time, Norman maintained in all his statements, did he fire his gun. The attack and his defense, he said, happened after the Guard gunfire, meaning his actions could not have provoked the soldiers to shoot.

Audiotape raises questions about Terry Norman’s role

The altercation and four .38 pistol shots that analyst Stuart Allen uncovered in October 2010 on the audiotape raise questions about Norman’s story that he didn’t fire and that the Guard’s fusillade preceded his assault.

Seventy seconds before the soldiers shoot, the recording captures shouts of “Kill him!” followed by sounds of scuffling and four distinct discharges. An earlier analysis of the tape also revealed an order for the Guard to prepare to fire. It is not clear how or if the altercation, pistol shots and firing order are related.

But as early as the afternoon of May 4, 1970, there were claims that Norman’s gun had been fired four times. There also were available witnesses whose stories contradicted some details — or raised questions about the timing — of Norman’s assault. However, police and government records indicate that investigators did not quickly, rigorously pursue those leads.

When Norman surrendered his pistol, he handed it to Kent State patrolman Harold Rice, who in turn gave it to Detective Kelley. TV newsmen Fred DeBrine and Joe Butano of Cleveland station WKYC and Guard Sgts. Mike Delaney and Richard Day observed the exchange.

The four said they saw a Kent State officer — DeBrine and Butano identified him as Kelley, Norman’s handler as an informant — crack open Norman’s pistol, look inside and exclaim, “My God, it’s been fired four times!” The TV crew and the two Guardsmen also said they heard Norman state that he may have shot someone.

Kent State student Tom Masterson has acknowledged being Norman’s assailant. He said the confrontation happened after the Guard stopped shooting, which jibes with part of Norman’s story, but insisted he was the only one involved. “There was definitely no group of students that attacked him,” Masterson, a retired San Francisco firefighter, said in a recent interview. “There wasn’t time.”

Another Kent State student, Frank Mark Malick, saw a photographer matching Norman’s description waving his pistol as the Guard fired and aiming in the same direction as the soldiers, although Malick said he couldn’t tell if the photographer was shooting.

The FBI looked little into Norman’s involvement until 1973, three years after the incident, when the Justice Department reopened the investigation. Even then the bureau acted reluctantly, at the insistence of Justice Department lawyers.

There is no evidence in the various investigative agencies’ files that anyone attempted to probe the inconsistencies in Norman’s various statements or between his versions and other witnesses’ accounts. According to Norman, Kent State police allowed him to type his own statement.

The FBI interviewed him twice, on May 4 and May 15, 1970, but in no greater depth than other witnesses. The bureau relied on the Kent State police department’s determination that Norman’s gun had not been fired.

The audiotape of the Guard shootings and their aftermath, along with TV footage shot by the WKYC crew of Norman surrendering his pistol, provides an improbably tight time frame within which Norman’s assault and his run for safety would have to fit for his story to be true.

In less than 1 minute and 49 seconds, Norman would have had to check on the injured student, be attacked, draw his gun, free himself from his assailants, then cross more than a quarter-mile of steep terrain to reach the Guard’s rope line.

Norman testified before a federal grand jury in December 1973 as part of the revived investigation. His testimony remains sealed, as is typical. But whatever was said, and whatever additional facts were uncovered, the grand jury did not indict him.

Federal investigators “never left a stone unturned” about Norman, former Assistant Attorney General Stanley Pottinger, who directed the inquiry, insisted in a recent interview.

Although neither Pottinger nor his second-in-command on the Kent State probe, former federal Prosecutor Robert Murphy, recalls details of what Norman said, they both were satisfied his actions on May 4 played no role in the Guard’s shootings. “As far as we were concerned at the time, it was a non-issue in the overall events of what happened that day,” Murphy said recently.

Terry Norman’s gun changes hands

Terry Norman’s .38-caliber pistol represented the best chance for investigators to determine if he fired shots on May 4, but there were abnormalities in its handling from the moment it was confiscated.

Terry Norman’s .38-caliber pistol represented the best chance for investigators to determine if he fired shots on May 4, but there were abnormalities in its handling from the moment it was confiscated.

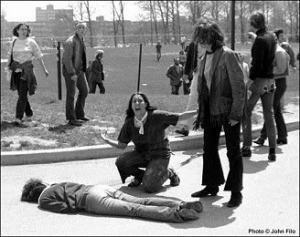

A Kent State University police officer takes a pistol from Terry Norman on May 4, 1970. Norman had been taking photos of protesters at an anti-war rally and said he carried the gun for protection.

Norman gave his weapon to Harold Rice, a Kent State patrolman he knew well enough to call “Hal.”

In his report of the incident, Rice wrote that he popped open the cylinder to confirm the gun was still fully loaded and sniffed the barrel to rule out that it had been fired, before handing the weapon to Detective Kelley. The TV footage shows none of this; in fact, the plastic face shield on Rice’s riot helmet precludes bringing a gun close to his nose.

Kelley, who directed Norman’s informant work for the department, carried Norman’s pistol back to the police station. Kelley, in his official statement and later interviews, was adamant that he’d never said Norman’s gun had been fired four times and that examination showed it was fully loaded. Other officers whom Kelley directed to sight- and smell-check the weapon backed him up.

In Norman’s sworn deposition from 1975, he said he had loaded his gun before May 4 with three hollow-point bullets, one armor-piercing round and one tracer round. When Kent State police turned Norman’s pistol over to the FBI on May 5, the bureau noted that it contained four hollow-point bullets and one armor-piercing round. The investigative record does not indicate that anyone noted or probed the discrepancy.

No one tested Norman’s hands or clothing for gunpowder traces, and there is no record that campus police questioned him about whether he had reloaded or searched him for extra bullets or expended shells.

The FBI later noted the Kent State police department’s failure to preserve a chain of custody of Norman’s gun, reporting that it had passed through four officers’ hands, and that at least one of them couldn’t recall when he’d had the pistol.

That casual police attitude extended to Norman’s overall gun-handling. Norman said campus police “unofficially” knew he often brought weapons to school — one had bartered with him on the premises for a rifle or shotgun — even though Police Chief Donald Schwatzmiller considered Norman “gun-happy and very immature” and wanted to bar him from campus. Northampton Police Chief Larry Cochran, who knew Norman from his part-time security job at the Blossom Music Center, had similar concerns.

An FBI check in 1973 determined that Norman lacked the proper paperwork to legally carry a concealed weapon during the May 4 rally. A former Portage County prosecutor told the bureau that Norman could have been charged, but the case would have been difficult to win.

Terry Norman’s FBI connection

Whether due to miscommunication, embarrassment or an attempted coverup, the FBI initially denied any involvement with Norman as an informant.

“Mr. Norman was not working for the FBI on May 4, 1970, nor has he ever been in any way connected with this Bureau,” director J. Edgar Hoover declared to Ohio Congressman John Ashbrook in an August 1970 letter.

Three years later, Hoover’s successor, Clarence Kelley, was forced to correct the record. The director acknowledged that the FBI had paid Norman $125 for expenses incurred when, at the bureau’s encouragement, Norman infiltrated a meeting of Nazi and white power sympathizers in Virginia a month before the Kent State shootings.

Norman insisted his FBI work lasted only about a month, including the Virginia mission and his photographing of campus dissidents.

But a Kent State classmate, Janet Sima, said recently that she accompanied Norman on a day trip to Washington, D.C., in December 1968 so he could attend a meeting he told her involved the FBI. “I felt like he couldn’t talk about it,” said Sima, who didn’t press Norman for details about the 90-minute appointment.

Tom Kelley, the Kent State detective who oversaw Norman’s campus informant work, told lawyers in 1975 that he suspected Norman had worked much more regularly for the FBI than the bureau had publicly acknowledged.

Terry Norman: From D.C. cop to former convict

Disillusioned with campus unrest and uncomfortable with his notoriety, Norman quit Kent State in August 1970 to become a Washington, D.C., policeman. His references included Detective Kelley and Akron policeman Bruce Vanhorn, with whom he had traded for the .38 pistol.

Alan Whitney, a labor leader who helped unionize the D.C. police force in 1972, said recently that Norman was one of about a dozen officers he worked closely with on the two-month campaign. Whitney said another officer told him that Norman sometimes boasted of playing a consequential role in the Kent State tragedy, including firing a gun. When Whitney asked Norman directly, Norman said he couldn’t talk about it.

Norman’s second wife, Sherry Millen, said she had no idea he had been on campus on May 4. Millen, who met Norman in the early 1980s when he was still a cop, said he was estranged from his family.

He told Millen that he’d helped get his first wife, Amy, a job with the CIA and that he had done occasional work for the spy agency. Norman liked shooting guns and talked about wanting to move to Costa Rica, become a mercenary and hunt down drug lords, Millen said.

After Millen and Norman divorced in the early 1990s, he ran into major legal trouble. In 1994, federal prosecutors accused Norman of leading a four-year scheme to bilk nearly $700,000 from the electronics company he worked for as a telecommunications manager.

At first with a partner, and later on his own, the ex-policeman set up shell companies and authorized payments for phony work. He used the money to buy a plane, a 41-foot boat, a recreational vehicle and a 20-acre homestead in Texas and to pad his and his new wife’s mutual funds.

By the time federal agents came after Norman and his third wife in the spring of 1994, Norman had already learned of the investigation. The couple had packed their RV with computers, passports, $10,400, and their four dogs and three cats. With Norman’s weapons and undercover training, the government considered him a serious flight risk.

Norman pleaded guilty to charges relating to conspiracy, mail fraud and money laundering. He served three years in prison. Reporters occasionally have tried to contact him, as the anniversaries of the May 4 tragedy come and go. He never has broken his silence. He and his wife live in a secluded area of North Carolina, on the edge of the Pisgah National Forest.